Why does the Last Supper in the Gospel of St. John (13-17)

contain no words of consecration?

Wojciech Kosek

| This paper is a translation of the article: Wojciech Kosek, Dlaczego Ostatnia Wieczerza w Ewangelii św. Jana (13-17) nie zawiera słów konsekracji? It was published by The Association of the Polish Biblical Scholars [Stowarzyszenie Biblistów Polskich] in W. Chrostowski, M. Kowalski (ed.), Kogo szukasz? (J 20, 15): Księga pamiątkowa dla księdza profesora Henryka Witczyka w 65. rocznicę urodzin [Whom are you seeking? (Jn 20: 15): Festschrift in Honor of Rev. Prof. Henryk Witczyk on his 65th Birthday] (series Ad Multos Annos 21), Warszawa 2021, ISBN: 978-83-8144-634-1, p. 226-257. |

This translation was first published on January 16, 2021,

on the Academia.edu website.

DOI of this paper:

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4445353

This translation was published here on January 17, 2021,

i.e., on the thirteenth anniversary of the defense of my doctoral dissertation.

Abstract.

To answer the title question of this article – Why does the Last Supper in the Gospel of St. John (13-17) contain no words of consecration? – one will mainly show that the Gospel of St. John has a six-element literary structure, the same as the Book of Exodus 1-18 has. This first step bases on the analyses of many exegetes and also on the particular comparative counting of numbers of words in all pericopes of four Gospels, which one performed in this paper. Then one will show four consecutive stages of Jesus’ life – presented by four consecutive pericopes of Jn 1:19-20:31 – as His four-stages Exodus from this world to eternity. Based on the thesis proved in the earlier papers that Ex 1-18 is the six-element treaty of the four-step covenant-making ceremony performed by God and Israel, one will show the whole life of Jesus on the earth as analogical to the Exodus described in Ex 6:2-15:21 – as performing consecutive four elements of the ceremony of making the New Covenant. It means John’s Gospel is the six-element treaty of the New Covenant. The key statement shows that The Pericope of Passion and Death (Jn 18-19) describes the irrevocable Jesus’ act of covenant-concluding, done through His passage between the darknesses of the Abyss-Death. It is analogical to pericope Ex 13:17-14:31 as a description of the irrevocable act of covenant-concluding by the passage of God and Israel between the waters of the Abyss-Red Sea. Thanks to these observations, one will get to know the answer to the question stated in the paper’s title.

Keywords:

Jesus, Eucharist, Holy Mass, consecration words, John’s Gospel, literary structure, Israel, Exodus, Passover, covenant, treaty, rite, celebration, Book of Exodus, liturgical anticipation, Bible, exegesis, after-liturgy prayer.

Table of contents:

- The literary structure of St. John’s Gospel according to exegetes.

- Examining the number of words in all pericopes of four Gospels to resolve the question about the structure of the Gospel of St. John.

- Israel’s Exodus as a covenant-making ceremony. Jesus’ Exodus as an analogical ceremony.

- The structure of Passover liturgy as a structure of covenant-making ceremony; Ex 1-18 as a covenant treaty.

- The structure of Eucharistic liturgy as the structure of the covenant-making ceremony; Jn 1-21 as the covenant treaty.

- The Book of Exodus 1-18 and the Gospel of St. John as covenant treaties – some significant word analogies and thematic analogies.

Introduction.

Discussing Luke’s pericope about the transfiguration of Jesus on the mountain, Benedict XVI points out that the Exodus (Lk 9:31 – ἔξοδος) about which Jesus spoke there with Moses and Elijah as an event to be completed soon in Jerusalem is the Cross of Jesus as His departure from this life, a passage through the ‘Red Sea’ of the Passion, and an entrance into the glory [1]. The fundamental expectation of the Law and the Prophets – emphasizes the Pope – is the Exodus that brings definitive liberation.

Unlike the Synoptics, the Evangelist John showed Jesus as the Son-Logos, whom God sent into the world to lead the people to salvation (cf. Jn 1:1-19) and who, at the same time, turned out to be not only the prophet and Messiah announced by prophets of Israel but also the Elijah [2]. In the Synoptics, it is John the Baptist who is the announced Elijah.

The Jews expected – and still expect – that Elijah would come during one of the Passover Feasts and lead Israel in a new Exodus into eternal life [3]. It is why during the third part of the Passover liturgy, they pour a special cup of wine for Elijah and then open the door: Elijah, if he comes during that Passover, will drink it before that expected Exodus [4].

What does St. John want to say, who – also unlike the Synoptics – links the drinking of this cup (ποτήριον) by Jesus-Elijah not with the Last Supper, but only with His Passion and Death (cf. Jn 18:11 vs. Mt 20:22-23; 26:27.39; Mk 10:38-39; 14:23.36; Lk 22:20.42) [5], and thus, as it will be shown, with the third main pericope of his Gospel?

What is the meaning of John’s record, unique against the background of the other Evangelists, belonging to the next pericope – the fourth main one – about the breathing of the Holy Spirit on the apostles by Jesus right after His Resurrection [6], and so giving them that Gift from the Father, on whom in the account of St. Luke (cf. Acts 2: 1-4) they had to wait until Pentecost? Are we to conclude in connection with it that the Evangelist wants to show in the fourth main pericope that there was fulfilled the announcement recorded in the first main pericope about Jesus as the expected Elijah, the one who baptizes with the Holy Spirit and fire (cf. Jn 1:33)? Does the announcement–fulfillment relation connect the first and fourth pericopes?

Going back even more in the text: can one identify The Last Supper Pericope (Jn 13:1-17:26) as the pericope of the granting of the law in the covenant scheme, considering that Jesus gives the new commandment within it (Jn 13:34), and at the same time this pericope is the second main one in the Gospel – just as the pericope of the granting of the law in the covenant treaties of the time of the Exodus of Israel? In light of the answer to this question, is it possible to understand in a new way the words of Jesus that it was He about whom Moses wrote (cf. Jn 5:46 and Deut 18:15)?

To answer these questions fully and, in consequence, to the title question of this article, we will present analyses, which will reveal two facts, the first literary, the second liturgical.

St. John made the six-element literary structure of the ancient covenant treaty the literary structure of his Gospel, just as did the author of the Book of Exodus 1-18. The covenant treaty, documenting the relations between two countries of the ancient Near East between the sixteenth and twelfth centuries B.C., had six pericopes, of which the four central ones were the report on the realization by the rulers of these countries of the four-element covenant-making ceremony; the outer ones were the introduction and the end.

St. John presents the entire temporal life of Jesus as the realization of the ancient covenant-making ceremony – the covenant that Jesus made between God and Himself as the representative of humanity. John’s presentation is analogous to that of the last redactor of the Book of Exodus 1-18, concerning this part of Israelites’ Exodus, which begins with the story of Jacob’s arrival with his family in Egypt and ends with the establishment of judges and departure of Jethro from camp near Sinai.

This work of God – bringing the Israelites out of the Egyptian captivity – was not only a saving event but also a realization of the covenant-making ceremony [7]. Jesus’ Exodus from this world to the Father is not only a saving event but also a covenant-making.

Then, the liturgical fact that is crucial to answering the title question of this paper is the identity of the four-element Passover liturgy [8] with the four-element covenant ceremony: the annual Passover makes its participants present in this four-element covenant ceremony which the four stages of the Exodus described in the Book of Exodus 6:2-15:21 were. Eucharist, built on the Passover rite, is the covenant-making ceremony which Jesus fulfilled by the Exodus from this world to the Father, and Jn 1:19-20:31 is the description of the realization of this ceremony.

This article will show in light of typological analysis [9] that the whole Gospel of St. John is a six-element covenant treaty, in which there are four pericopes between Prologue and Epilogue, describing successive acts of the ceremony once fulfilled historically by Jesus. It is this ceremony that is made present in each Eucharistic celebration in the four successive main parts of the liturgy. The Gospel of St. John as a whole reveals no signs of the Eucharistic liturgy but what is under them. This Gospel, therefore, reveals the depth of the liturgy, the meaning of signs. It is the reason why in this Gospel, the Last Supper pericope (Jn 13-17) does not convey the words of consecration (cf. Mt 26:26-28; Mk 14:22-24; Lk 22:19-20; 1Cor 11:24-25): in the covenant treaty scheme, it is not the description of the very act of the covenant-making, but the description of the presenting of the covenant partners and of the act of bestowing the covenant law. Only the next pericope is to show the act of covenant-making: the reality of the Passion and Death of Jesus, Who makes a covenant by passing through the Abyss-Death, analogically as God, present in the sign of the pillar of fire/cloud, with Israel made a covenant by passing through the waters of the Abyss – the divided Red Sea.

1. The literary structure of St. John’s Gospel according to exegetes.

Contemporary exegetes agree that the Gospel of St. John has a literary structure that is difficult to discover unambiguously. Different proposals for dividing the text and naming individual parts depend on the criterion according to which the exegete undertakes to discover this structure. Nevertheless, many proposals reveal a common general concept that differs only at the more detailed division level. It is worth seeing some of them.

Biblia Tysiąclecia 4 [The Millennium Bible [10]] (Poznań-Warszawa 1980) in the introduction to the Gospel of St. John, and similarly Biblia Poznańska 3 [The Poznań Bible [11]] (Poznań 1994):

| 1-12 | The Book of Signs |

| 13-21 | The Book of Passion |

E. Szymanek [12] clearly distinguishes Jn 13:1-17:26 as the Last Supper pericope. He also claims that chapter 21 is written not by St. John but by his disciples, who added it to the text ending at 20:31 [13]. J. Kręcidło [14], following G. Mlakuzhyil, claimed in 2006 that Jn 13:1-17:26 is a literary whole – a six-elements chiasmus.

| 13:1-38+ | The Symbolic Act, the Prediction of Betrayal |

| 13:31-14:31 | The Prediction of Peter’s Denial. First Farewell Discourse |

| 15:1-17 | The Allegory of the Vine, the Commandment of Love |

| 15:18-16:4d | The Hatred and Persecution by the World, the Testimony of Disciples |

| 16:4e-33 | The Second Farewell Discourse and an Announcement of the Departure |

| 17:1-26 | Prayer in the Hour of Passion, Death, and Resurrection |

However, in the second edition of his work, G. Mlakuzhyil [15] came to the conclusion that this is a five-element chiasmus, namely:

| 13:1-38+ | Feet-Washing, Prediction of Betrayal & Denial |

| 13:31-14:31 | First Part of the Farewell Discourse |

| 15:1-16:4d | The Commissioning Discourse |

| 16:4e-33 | Second Part of the Farewell Discourse |

| 17:1-26 | Prayer of the Hour [of Passion – Death – Resurrection] |

M. Uglorz, the translator of this Gospel [16], gives more detailed division:

| 1:1-18 | Initial hymn (prologue) |

| 1:19-4:54 | First meetings and first signs |

| 5:1-10:42 | Revelation and judgment: miracles and speeches |

| 11:1-12:50 | Towards the decisive hour |

| 13:1-17:26 | Jesus’ long farewell |

| 18:1-19:42 | Passion and death as a revelation of the glory |

| 20:1-21:25 | Resurrected Jesus |

Biblia Paulistów [17] first gives a division into two essential parts:

| 1:19-12:50 | Narrative about Jesus’ revelation to the Jews through signs |

| 13:1-20:31 | Teaching directed to disciples |

and then adds that there are two more parts:

| 1:1-18 | Prologue that begins the Book |

| 21 | Epilogue added to the whole at its end |

The first main part consists of the following subparts:

| 1:19-7:9 | Jesus often changes His place of stay (Jerusalem, Galilee). The Jews’ objections do not arouse until the situation described in 7:1-9 | |

| 7:10-12:50 | Jesus is in Jerusalem or the surrounding area. There is increasing conflict with Jews. This part consists of two fragments: | |

| 7:10-10:42 | The time of teaching | |

| 11:1-12:50 | Direct preparation for the dramatic events of Jesus’ last Passover in Jerusalem | |

The second main part consists of the following parts:

| 13:1-14:31 | The Last Supper |

| 15:1-17:26 | Jesus’ extensive speech |

| 18:1-19:42 | Description of the Passion |

| 20:1-31 | Description of the Resurrection |

Exegetes from other countries also propose different solutions.

F. J. Moloney [18] notes four main parts and Epilogue:

| I. 1:1-18 | The Prologue |

| II. 1:19-12:50 | The ministry of Jesus or “The Book of Signs” |

| A (1:19-51) | The first days of Jesus |

| B (2:1-4:54) | From Cana to Cana |

| C (5:1-10:42) | The feasts of the Jews (5 holidays are pointed out) |

| D (11:1-12:50) | Jesus turns toward “the hour” |

| III. 13:1-20:29 | The account of Jesus’ final night with His disciples, the Passion, and the Resurrection |

| A (13:1-17:26) | The last discourse |

| B (18:1-19:42) | The Passion |

| C (20:1-29) | The Resurrection |

| IV. 20:30-31 | The solemn conclusion of the Gospel |

| V. 21:1-25 | Epilogue |

C. G. Kruse [19]:

| 1:1-18 | Prologue |

| 1:19-12:50 | Jesus’ work in the world. One also calls this part The Book of Signs, [20] because it contains the description of seven signs-wonders of Jesus. |

| 13:1-20:31 | Jesus’ return to the Father |

| 21:1-25 | Epilogue |

Kruse divides the part “Jesus’ return to the Father” into three subparts and rightly states that such division is easy to see [21]:

| 13:1-17:26 | The Last Supper with the farewell discourses and Jesus’ prayer |

| 18:1-19:42 | The Passion narrative |

| 20:1-31 | The Resurrection narrative |

The author notes [22] that concerning the work of Jesus in the world (1:19-12:50), one of the popular approaches is to see 1:19-51 as an introduction to the ministry of Jesus, then 2:1-4:54 as an independent unit which begins and ends with Jesus’ miracle in Cana in Galilee. The next long passage, 5:1-10:42, is arranged around the Jewish festivals (cf. 5:1; 6:4; 7:2; 10:22) and then 11:1-12:50 functions as a bridge closing the account of Jesus’ ministry in the world and preparing readers for the third major part of the Gospel, His return to the Father (13:1-20:31). Kruse notices that distinguishing the part “From Cana to Cana” is problematic because the Evangelist does not attach much importance to the fact that Jesus performed two miracles in Cana. He also notices that the structuring of 5:1-10:42 around Jewish festivals does not take into account that throughout the whole Gospel, and not only in 5:1-10:42, the Evangelist consistently uses Jewish festivals and Jesus’ actions concerning them as chronological markers (2:13:23; 3:22; 4:4:43; 5:1; 6:4; 7:2:10:14:37; 10:22:40; 11:55; 12:1:12:20; 13:1;18:28; 19:31:42). He concludes – and this is also reflected in his analyses – that it is best to treat 1:19-12:50 as one long presentation of the ministry of Jesus in the world, marked by signs and public discourses.

Kruse distinguishes six pericopes in the Gospel of St. John. The next section of this article will show that this is justified – and based on arguments that he did not know!

2. Examining the number of words in all pericopes of four Gospels to resolve the question about the structure of the Gospel of St. John.

Many of the proposals of dividing the Gospel of St. John put exegete before the task of trying to decide where the truth is. Above all, scientists agree that the Prologue (Jn 1:1-18) differs in its literary genre from the rest of the text: the Prologue is an anthem, while the next part, beginning from verse 1:19, is a narrative. Furthermore, chapter 21 is referred to as the Epilogue, the closing part of the Gospel, although, paradoxically, it is after the Gospel’s conclusion in verses 20:30-31. Some scholars – in connection with this paradox – regard the Epilogue as a text not belonging to the Gospel of John. However, in light of Catholic exegesis’s principles [23], the entire canonical text of the Gospel, including the Epilogue, is God’s word. The same applies to Prologue, which some erroneously consider not to belong to the Gospel because of its different literary form or its similarity (alleged!) to Gnostics’ philosophical tractates.

The Gospel of John, therefore, has two outer parts: Prologue (1:1-19) and Epilogue (21:1-25). The scholars divide the middle part of the text variously. Nevertheless, the idea that it consists of two parts prevails today. 1:19-17:26 shows Jesus’ activity in the world, while 18:1-20:31 Jesus’ departure from the world. However, a closer look at the two parts allows dividing each of them also into two parts. Namely, 1:19-12:50, The Book of Signs, shows the work of Jesus teaching and confirming the authenticity of His coming and mission from the Father by wonderful signs before the disciples, opponents, and the multitudes; 13:1-17:26, The Last Supper Pericope, shows the Last Supper, being the Passover Feast of Jesus and the twelve disciples. 18:1-19:42, The Book of Passion, represents the passage of Jesus from the Cenacle to Golgotha; it includes Jesus’ prayer in the Garden, arresting Him, unjust judgments over Him, leading to sentence Him to death, and finally His last moments until He offered life on the cross on Golgotha. 20:1-20:31 as The Book of Glory shows the presence of Risen Jesus, who gives the Holy Spirit to His disciples.

One should note that St. John, unlike the Synoptics, dedicated an extensive text to the Last Supper. It is the reason why it does not seem to be in line with the Evangelist’s intention to understand this text as just a part of some larger whole – pericope – and consequently not to notice that just this text is a literary whole, one of the basic pericopes constituting the literary structure of this Gospel.

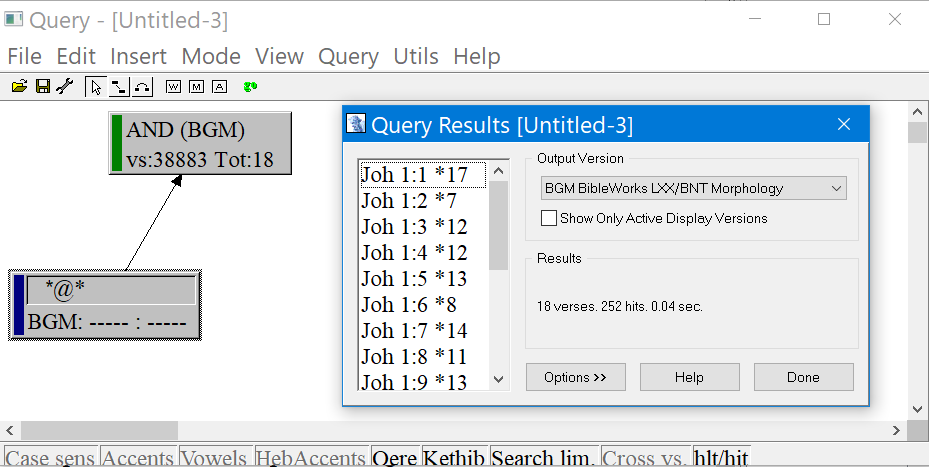

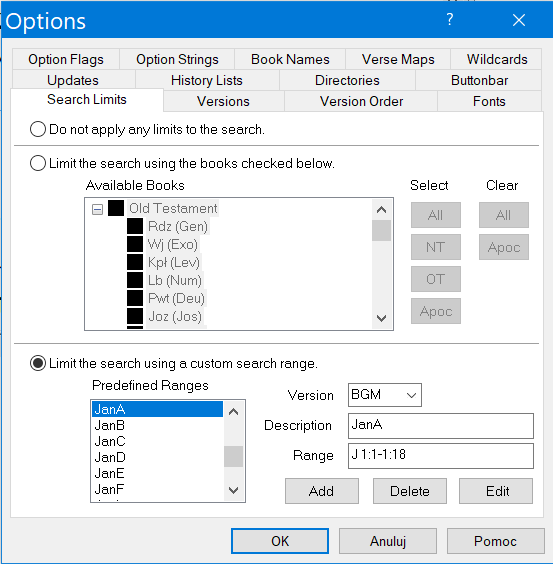

To get a reliable answer to the question of whether this is true, we conducted research using the computer program BibleWorks 6.0. for BGM (i.e., for the Greek Bible, where all successive words of the text are present in their basic form, the so-called lemma), typing the .*@* command in Command Center and running Advanced Engine:

One did this operation for all basic structural parts of four Gospels, whereby one set the so-called Search Limit for each part before commanding Go. For example, for John 1:1-18:

One can see in the table below that St. John, unlike the Synoptics, really dedicated a very extensive pericope to the Last Supper. For each Gospel, the table shows the number of all words (Greek) and the number of words of The Last Supper Pericope; the third column, basing on this, shows the percentage share of words of this pericope in the total number of words of the Gospel. Because all the Synoptics, unlike St. John, precede the Last Supper description with several verses of Jesus’ command to the disciples to prepare the Passover, we joined these verses with that description in our analysis.

| The whole Gospel | Preparation + the Last Supper | (Preparation + the Last Supper)/ the whole Gospel |

Mt 18346 | Mt 26:17-19 + 26:20-35 61 + 268 = 329 | 329/18346*100 = 1.8% |

Mk 11304 | Mk 14:12-16 + 14:17-25 99 + 152 = 251 | 251/11304*100 = 2.2% |

Lk 19482 | Lk 22:7-13 + 22:14-38 96 + 419 = 515 | 515/19482*100 = 2.6% |

Jn 15635 | Jn 13:1-17:26 2822 | 2822/15635*100 = 18.1% |

The table shows that in the Gospel of St. John, the Last Supper description contains 18% of its entire Greek text, while the other Gospels have less than 2% – 3%, that is, over nine – six times less.

However, it is worth answering another question: what is the comparison of analogical calculation results concerning the description of Jesus’ Passion and the description of His Glory? The answer is in the table below:

| The whole Gospel | Passion | Glory | Passion/ the whole Gospel | Glory/ the whole Gospel |

Mt 18346 | Mt 26:36-27:66 1704 | Mt 28:1-20 329 | 1704/18346*100 = 9.3% | 329/18346*100 = 1.8% |

Mk 11304 | Mk 14:26-15:47 1426 | Mk 16:1-20 341 | 1426/11304*100 = 12.6% | 341/11304*100 = 3.0% |

Lk 19482 | Lk 22:39-23:56 1351 | Lk 24:1-53 818 | 1351/19482*100 = 6.9% | 818/19482*100 = 4.2% |

Jn 15635 | J 18:1-19:42 1609 | J 20:1-31 615 | 1609/15635*100 = 10.3% | 615/15635*100 = 3.9% |

Based on this table, we can see that St. John’s Gospel does not stand out from other Gospels in terms of the greatness of the description of the Passion of Jesus and the description of the Glory of Jesus. The same is also indicated by the sum of these two descriptions for each of the Gospels: 11.1%, 15.6%, 11.1%, 14.2%. We can see against this background that St. John’s description of the Last Supper is extremely extensive. St. John intentionally expanded this description to point out that it is one of the main parts of his work’s literary structure.

To complete the analyses is also worthwhile to carry out a study of the number of words in two parts: 1) Introduction – existing as the part dedicated to The childhood of Jesus in St. Matthew and St. Luke, and as Prologue in St. John; there is no such part in St. Mark, 2) Activity – this part of each Gospel, where is the description of Jesus’ activity until the Last Supper.

| The whole Gospel | Introduction (Childhood or Prologue) | Activity | Introduction/ the whole Gospel | Activity/ the whole Gospel |

Mt 18346 | Mt 1:1-2:23 893 | Mt 3:1-26:16 15091 | 893/18346*100 = 4.9% | 15091/18346*100 = 82.3% |

Mk 11304 | – | Mk 1:1-14:11 9286 | – | 9286/11304*100 = 82.2% |

Lk 19482 | Lk 1:1-2:52 2035 | Lk 3:1-22:6 14763 | 2035/19482*100 = 10.5% | 14763/19482*100 = 75.8% |

Jn 15635 | J 1:1-18 252 | J 1:19-12:50 9790 | 252/15635*100 = 1.6% | 9790/15635*100 = 62.6% |

Considering, furthermore, that the Epilogue has 547 words, i.e., 547/15635 * 100 = 3.5%, we can include in the table a summary of the percentage share of individual parts in the total text of each Gospel:

Introduction (Childhood or Prologue) | Activity | Preparation + Last Supper | Passion | Glory | Epilogue | |

| Mt | 4.9% | 82.3% | 1.8% | 9.3% | 1.8% | – |

| Mk | – | 82.2% | 2.2% | 12.6% | 3.0% | – |

| Lk | 10.5% | 75.8% | 2.6% | 6.9% | 4.2% | – |

| Jn | 1.6% | 62.6% | 18.1% | 10.3% | 3.9% | 3.5% |

At the end of the numerical analyses, it is worthwhile to show in the table the text of the four Gospels divided into three parts. Namely, in the central part is the pericope of Preparation and Last Supper; in the first part are the pericopes preceding this central one; in the third part are the pericopes following this central one.

Introduction (Childhood or Prologue) plus Activity | Preparation + Last Supper | Passion plus Glory plus Epilogue | |

| Mt | 87% | 2% | 11% |

| Mk | 82% | 2% | 16% |

| Lk | 86% | 3% | 11% |

| Jn | 64% | 18% | 18% |

| (Mt+Mk+Lk)/3 | 85% | 2% | 13% |

The last table shows that:

- The description of Jesus’ life until the Last Supper takes about 80% of the text in the Synoptics, while about 60% of St. John’s, viz. about 20% less.

- The description of the Last Supper takes up a negligible part of the text in the Synoptics, while it takes almost 20% of St. John’s text.

- The description of the events after the Last Supper takes about 15% of the text in all the Gospels.

- The last row of the table shows what roughly would be the percentage division of the three parts of St. John’s Gospel if its author kept the averaged proportions of the Synoptics.

It is evident that St. John intentionally reduced the percentage share of the description of Jesus’ activity by 20% in relation to the whole Gospel in order to enlarge the description of the Last Supper to about 20% in relation to the whole Gospel and to give it the rank of one of the main literary parts of the work.

We can conclude in the result of the analyses that the Gospel of John has six pericopes: 1:1-18: The Prologue; 1:19-12:50: The pericope of signs; 13:1-17:26: The Last Supper Pericope or the pericope of the Passover Feast; 18:1-19:42: The pericope of Jesus’ Passion and Death; 20:1-20:31: The pericope of Jesus’ Glory; 21:1-21:25: The Epilogue.

The given division takes into account the essential difference – overlooked by some exegetes – between the stage of Jesus’ departure from this world through Passion and Death and the stage of His Glory, for there is a fundamental disproportion between the stage belonging to the events of Jesus’ temporal life and the stage which is part of a completely new – eternal – existence, although giving itself to people in temporal time. Therefore, there is a fundamental difference between the pericope of Jesus’ Passion and the pericope of His Glory.

One can easily notice that Prologue differs from the next pericope (The Book of Signs: 1:19-12:50) by its literary genre and the fact that it has the end strictly before that pericope – being a chiastic structure [24], it begins in 1:1 and ends in 1:18. In turn, the separation of the pericope of Glory from the Epilogue is easily noticeable thanks to the evident literary effort of the author (or the last editor) to write the end of the Gospel, i.e., of the essential part of it, in the verses ending the pericope of Glory. These observations allow seeing that the Epilogue and the Prologue are special pericopes used to frame the four central pericopes.

On the other hand, the pericope of signs differs from the pericope of Last Supper in the aspect of the move. Namely, in the pericope of signs, Jesus moves from place to place, enters into relations with many people, makes signs confirming the origin of His mission from the Father. In contrast, in the pericope of Last Supper, Jesus is all the time in one place, in the Cenacle, among the closest disciples, does not make any supernatural signs, i.e., miracles, except the very natural sign of the washing of the disciples’ feet to reveal His humble love.

3. Israel’s Exodus as a covenant-making ceremony. Jesus’ Exodus as an analogical ceremony.

An in-depth analysis of the Book of Exodus 1-18 showed that Israel’s Exodus from Egypt was not only a historical event that brought God’s people out of the land of bondage to the land of freedom. God intended to make the first part of that Exodus – viz. the passage from Egypt to the place near the foot of God’s Mount Horeb – served Him to establish a particularly close relationship with the people: a covenant.

However, this is not about the Sinai covenant, which took place not until when the people, led by God visible in the signs of fire and cloud, after crossing the Red Sea and three months of wandering, arrived near this God’s Mountain. About what covenant, then, are we talking here? Was there a covenant between God and Israel earlier than the commonly known The Covenant of the Ten Words?

Yes, God has previously made a covenant with Israel! [25] The passage of God in a sign of fire/cloud and the passage of people of Israel with Him between divided waters of the Red Sea is the irrevocable act of the covenant-making, the third of the four elements of the covenant-making ceremony from about the sixteenth to the twelfth century B.C. This ceremony had the following parts [26]:

- The presentation of the covenant parties, with particular emphasis on the advantages and merits of the stronger one.

- The bestowing of the covenant clause (law) on the weaker party by the stronger one. The covenant clause’s essence is to guarantee that the weaker party will celebrate the day of the covenant-making every year, remembering the acceptance of a relation of submission to the stronger party.

- The performing of the irrevocable act of the covenant-making by the passage of both parties between halves of divided animals on the ground soaked with their blood.

- The fulfillment of covenant promises (e.g., giving land to a weaker partner) and commemorating the covenant (e.g., by making a mound, by placing the covenant treaty in sanctuaries of both sides).

The particular stages of the covenant-making ceremony were carried out in Israel’s Exodus from Egypt and in the Exodus of Jesus as follows:

Re A. Ex 6:2-11:10: God gives Israel the promises of the covenant (liberation, land bestowing) and reveals His greatness and splendor as a stronger contractor through the miraculous signs-plagues; the role of presenting the weaker contractor is performed above all by the genealogy of Moses and Aaron (Ex 6:13-27). In the Gospel of St. John pericope 1:19-17:26 as the so-called “Book of signs” has an analogous function [27]. On the one hand, essential for the typology of both situations, miracle signs are to testify to the greatness of God as their originator and thus to become an opportunity to believe in His power and submit to Him. On the other hand, God knows in advance the persistent disbelief of the opponents – Egyptians and Judeans from Jerusalem – as the result of their hard hearts and acts of rejecting the meaning of signs [28].

Re B. Ex 12:1-13:16: This is the pericope of law in which God imposes a covenant law on Israel, obliging Israel to annually celebrate the day of her entry into the relationship of submission to Him as a sovereign. This law requires the Passover’s annual celebration on the night of the 15th day of the month Abib, eating a lamb with unleavened bread and bitter herbs. Contrary to modern ‘proofs’ of the need to break the text of Ex 12:1-13:16 into alleged sources, one proved its literary consistency as the pericope of law thanks to the specific interweaving of the speeches of God and Moses in it [29]. Furthermore, one showed that the description of the Israelites’ departure from Egypt, present in the middle of this pericope, also serves for legislative purposes (it is an explanation of the obligation to eat unleavened bread during the Passover and during the seven-day Feast of Unleavened Bread – the Israelites came out with dough not yet acidified); it is not to describe the next (third) stage of Exodus [30]. Two issues of this pericope – bestowing the law and explaining it by describing the departure – are intertwined. A similar intertwining is in The Last Supper Pericope of Jesus with the Apostles (13:1-17:26): it is the pericope of law because Jesus gives the disciples a new law within it (13:34) – the duty to love as He loves and therefore without retreating from the sacrifice of one’s own life when one has to testify of obedience to God above love for oneself and people. Because after the end of this supper, Jesus will enter the way of giving His life out from love for Father, His repeated references to the imminent departure from this world are not only a statement about the near-death but also an explanation of how the disciples should obey the law of love which He now bestows on them. The washing of their feet and explaining this act (13:5-17) already served the same purpose. Jesus’ speeches about the near presence of the Father, the Holy Spirit, and His with the disciples, and His prayers have the same purpose: they strengthen the disciples’ hearts to trusting God, who is the helper of those loving as He commands them. Jesus’ words concerning hostility in the hearts of those who do not believe and do not love God have the same purpose: they show the realism of love from the perspective of the taking of their life by those far from God and His law of love.

Re C. Ex 13:17-14:31: The act of the contractors’ passing through a ground soaked with the blood of animals, and thus through the world of death, was the culturally established third element of the covenant-making ceremony [31]. It was according to this ceremony that God first made a one-sided covenant with Abram – in the sign of fire and smoke (after four hundred and thirty years, the sign of pillar of fire/cloud was visually analogous to them), He passed between the halves of the animals, which Abram split in two and placed each half opposite the other on the ground. It was then that God announced to the Patriarch that his descendants would be in captivity for four hundred years in some country from which God would lead them out – it happened during Moses’s life (cf. Gen 15:13; Ex 12:40-41).

The passage through the world of death – between halves of killed animals, on a land soaked with their blood – was realized in a specific way in the covenant of Exodus: God and Israel passed between halves of the split sea, on its exposed bottom, i.e., on the bottom of the abyss of waters, and the abyss in Biblical revelation is precisely the world of death. According to the prophet Isaiah’s revelation (cf. Isa 51:9-10), God cut [32] the sea as a specific animal – the Rahab, i.e., a huge animal – to lead His people towards freedom. The passage of God between the halves of animals, cut by Abram in two, and the passage of God and Israel between the halves of sea-Rahab, cut by the Lord in two, took place at night.

Jesus makes an analogous passage in the darkness through the world of death – through the Abyss: it was night (cf. Jn 18:3), when, leaving the Cenacle, He began the next stage of His Exodus, a stage also spiritually characterized by the darkness of night (cf. Jn 9:4; Lk 22:53); there was darkness when he was dying on Golgotha during the eclipse of the sun (cf. Lk 23:45); by giving His life on the cross, descending into the darkness of the Abyss (cf. Job 38:16-17), Jesus passes through it, in order to come out of it just three days later to a new reality, to the supernatural state of existence. Just as Israel’s passage through the Abyss-sea was not only an act of marching to the other side to live in freedom from the Egyptians-oppressors but also an act of making a covenant, the same is with Jesus’ act of dying, that is, His passing through the Abyss-Death until the morning of the Resurrection (cf. Ex 14:24 and Jn 20:1).

Re D. Ex 15:1-21: fulfillment of covenant promises. Through the liturgical chanting of the hymn – by the power of liturgical anticipation – the promise of God to give Israel her land is accomplished; at the same time, Israel confesses that God is her King, the Lord. Writing down the fact that God and Israel made covenant is accomplished extraordinarily – through a song written in the hearts of the People. An analogy in St. John’s Gospel: just as after passing through the Abyss of waters in the night Israel in the morning has full of joy and full of the new life and sings a song of praise for God (cf. Ex 15:1-21; about glory – δόξα – in verses 7 and 11), the same is in the life of Jesus in the morning of Resurrection, after passing through the Abyss of Death. Jesus has a new kind of life! Father of Jesus had surrounded Him with a unique glory, “with the glory that He had before the world began,” as He announced in the Cenacle (cf. Jn 17:5): the new life of the Risen Jesus is this glory.

Furthermore, Jesus Himself gives the Father glory by showing Himself – as the living person – to His disciples. For apostolic catechesis from the beginning indicated that it was God who raised Jesus from the dead (cf. Acts 3:15). Jesus Himself spoke about His miracle of raising Lazarus to life as an act towards the glory of God so that the Son of God could be glorified through it (cf. Jn 11:4). Moreover, all miraculous signs of healing served to show the glory of the Father and the Son (cf. δόξα in Jn 2:11; 7:18; 8:50.54; 11:4.40). The greatest of these signs – the Resurrection of Jesus – most sublimely shows the glory of God and gives glory to God.

What is more, St. John, exceptionally in comparison with other Evangelists, shows Jesus breathing the Holy Spirit into the disciples just now (cf. 20:22). Therefore, Jesus gives the Holy Spirit now, i.e., when He has been glorified in the fourth stage of the covenant ceremony – He fulfills the promise He made in the first stage of the ceremony (cf. 7:39). Pericopes first and fourth are in the relation announcement – fulfillment.

Just as the four parts of the Exodus from Egypt, with the irrevocable act of passing through the Abyss-Sea, the four parts of Jesus’ Exodus, with the irrevocable act of passing through the Abyss-Death, are not only stages of His life, but the realization of the four elements of the covenant-making ceremony. Not only did Jesus die as an atoning sacrifice for the sins of the world, but during this act, He made a New Covenant exactly when He was giving His life on Golgotha, descending into the Abyss and leaving it. The covenant made in the Blood of Christ is the one He made in the act of passing through the ‘Red Sea’ of His Blood. We can say this passage of the Eternal Light between the darkness of the Abyss towards eternal life split the Abyss into two (cf. Jn 1:4-5). Jesus-God did the same work with Abyss-Death as He did ages before with Abyss-Sea (cf. Ex 14:21-22).

4. The structure of Passover liturgy as a structure of covenant-making ceremony; Ex 1-18 as a covenant treaty.

Studies of the Passover liturgy have shown [33] that it has the structure of a covenant-making ceremony, which was in force between the sixteenth and twelfth centuries before Christ, i.e., during the Exodus of Israel. The Book of Exodus 1-18 is a treaty of this covenant; namely, it reports the course of the four-element ceremony in four inner pericopes, framed by two pericopes.

In the successive four parts of its rite, the Passover takes [34] its participants into the time of the successive four stages of the Exodus from Egypt, the stages written in the successive four pericopes of the Book of Exodus: 6:2-11:10; 12:1-13:16; 13:17-14:31; 15:1-21.

The four main stages of the Exodus are:

- The time before the Passover supper in Egypt

- The time of the Passover supper in Egypt

- The time of the march out of Egypt, from the place of eating the Passover supper. It is the passage to the sea and between its halved waters

- The time of singing hymns at the other side of the sea, at the side of freedom

A literary frame surrounds the main stages:

- The preparation stage, described in Ex 1:1-6:1. It is represented in Passover tradition by the custom of seeking and removing acid from the house and in the custom of lighting the Passover candle

- The crowning stage of the Lord’s work, described in Ex 15:22-18:27. It is represented in Passover tradition by so-called post-seder: until morning, pious Jews stay on singing in honor of the Lord and pondering the revelation of His graciousness to Israel through the work of bringing her out of bondage.

The four parts of the Exodus are made present in sequence by the four parts of the Passover seder:

- The Passover haggadah (story), chanting of the first part of Hallel, i.e., Psa 113-114. This part serves primarily to show God as the stronger contractor of the covenant, and His blessings to Israel, still in need of His help.

- Eating dishes prescribed by the law, i.e., lamb, unleavened bread, bitter herbs, and then a casual feast. This part serves primarily to accept/implement (by the eating) the Law of the Covenant by the Israelites: each year by eating these foods, they remember about God, who at that very day led them out of the bitter situation of bondage, commanding them in advance to eat the lamb in houses anointed with its blood.

- Eating an unleavened Afikoman, which the leader breaks and gives each of the Passover participants. Afikoman – אֲפִיקוֹמָן – its (וֹ) bottom (אֲפִיק) is manna (מָן) – etymologically reveals the fact that now the participants of Passover participate in the passage of the Fathers under God’s guidance on the exposed bottom of the Sea of Reeds (יַם־סוּף) / Red Sea (θάλασσα ἐρυθρᾶς), at the bottom of the Abyss. In this part, one fills the cup of Elijah [35], under whose leadership the Exodus may be renewed on that very night, and then opens the door and asks God to pour out His wrath (חֲרוֹן) right now on hostile nations – it is the liturgical sign of the beginning of the march-out [36]

- Worship of God by singing the second part of Hallel, i.e., Psa 115-118, singing other songs. In this part, they participate in the singing of hymn (cf. Ex 15:1-21) by Fathers after crossing the sea. Within this hymn (cf. Ex 15:16-17), Israel had already, through the liturgical anticipation, received the Promised Land, had already entered it, had already built a temple of God – although this was not supposed to happen historically until after forty years of wandering (as a result of Israel’s disobedience to God).

The four parts of the Passover are surrounded by the liturgical buckle of pre-seder and post-seder, i.e., preparatory customs (e.g., searching for and removing all acid) and rituals that pious Jews perform even until the morning (they sing, contemplate the meaning of celebrated events) – long after the end of the prescribed acts of the official ceremony (so-called seder).

The Passover makes its participants successively participants of the four stages of the Exodus from Egypt, and at the same time, participants of the four stages of the covenant-making ceremony.

5. The structure of Eucharistic liturgy as the structure of the covenant-making ceremony; Jn 1-21 as the covenant treaty.

Comparative studies [37] of the Passover liturgy and the Eucharistic liturgy have shown that both have the same structure because Jesus instituted the Eucharist as the new Passover; they are structures of the ancient covenant-making ceremony.

Therefore, the Eucharist has the same structure and logic as the Passover. The Eucharist also has four parts (the first two of which are called the Liturgy of the Word and the next two are the Liturgy of the Eucharist: cf. e.g., General Instruction of the Roman Missal, No. 28, 120-170): The biblical readings, the homily, the profession of faith, the prayer of faithful:

- The reading and singing of Scripture texts, homily, confession of faith. This part serves to show God above all as the stronger contractor of the Covenant, who declares that He will bestow graces on the people who still need His help. The first main pericope of St. John’s Gospel (1:19-12:50) as The Book of Signs also serves this purpose.

- The prayer of faithful. This part serves to adopt and realize the covenant’s law, the covenant of mutual love of God and men and men among themselves. Also, the second main pericope of St. John’s Gospel (13:1-17:26) as The Last Supper Pericope serves this purpose: it shows Jesus who – through His presence with His disciples, and an example of service, explanation, and prayer – purifies them and implants them in Himself, in the love of His heart. We will discuss it in more detail in the next section of this article.

- Transubstantiation as making present the Salvific Death of Jesus, i.e., His Passing through the Abyss; eating of the unleavened Host (given by the priest as the leader to each Eucharist participant) as an act of participation in that Jesus’ Passing through the Abyss. One drinks the cup of Elijah-Jesus here. As shown earlier, the third main pericope of John’s Gospel (18:1-19:42) as The Book of Passion serves to describe the realization of this goal of the third stage of Jesus’ life – of Jesus’ Exodus.

- The glorification of God after the consumption of Holy Communion (cf. General Instruction of the Roman Missal, No. 37: song after communion). This part is the participation of People in the glory of Jesus coming out of Abyss, in the glory of Risen One, who appears to disciples and gives them Holy Spirit as a gift from Father in response to His love. Jesus already gives eternal life to believers here. As shown earlier, the fourth main pericope of St. John’s Gospel (20:1-20:31) as The Book of Glory serves to describe the realization of this goal of the fourth stage of Jesus’ life.

These four parts are framed by two parts: the introductory rites and the concluding rites; pious faithful extend the latter part in their adoration prayer after Holy Mass [38]. In the Gospel of St. John, two pericopes – Prologue and Epilogue – are analogical to those two parts. The Prologue, in analogy to Ex 1:1-6:1, shows Jesus’ entry into this world (from which He will be coming out through performing four stages of the covenant-making ceremony – as described in Jn 1:19-20:31).

The analogy between four parts of Passover and four parts of Eucharist is particularly evident in the sign of breaking Paschal Afikoman as unleavened bread [39] when the liturgical participants are moved into the most crucial time of covenant-making – to time of passing through Abyss of Red Sea / Abyss of Death of Jesus [40].

Just as Ex 1-18 is the treaty of the covenant of Passover/Exodus of God with Israel, so the Gospel of John is the treaty of the covenant of Eucharist/Exodus of God with Jesus as representative of humankind.

6. The Book of Exodus 1-18 and the Gospel of St. John as covenant treaties – some significant word analogies and thematic analogies.

The Book of Exodus 1-18 as the treaty of the covenant made in the passage between halves of sea-Rahab has six pericopes, of which the four central ones are a description of the realization of the successive four elements of the covenant-making ceremony, and the two outermost ones are a description of the preparatory stage, preceding the day of the beginning of the ceremony, and the finishing stage, following the end of the ceremony. Can we understand the course of Jesus’ life by analogy with the Israelites’ history, presented in the Book of Exodus 1-18? Yes, the Gospel of St. John has six main parts clearly outlined.

The Prologue and Epilogue are a literary frame for the four middle parts. The Prologue shows the preparatory stage, preceding the day on which Jesus began the first of the four elements of the covenant ceremony. The Epilogue is the finishing of the treaty.

The Prolog of the Book of Exodus speaks about the entry of Israel’s Fathers into Egypt’s land, from which their descendants would be coming out in a four-stage Exodus (Ex 6:2-15:21). The Prologue of John’s Gospel speaks about the entry of Logos into this world, from which He would be coming out in a four-stage Exodus (Jn 1:19-20:31).

The theme of the subsequent central parts of this Gospel is the description of the successive four stages of the covenant-making ceremony, namely:

A. Jn 1:19-12:50. The Book of Signs/Wonders, analogically to the Book of Exodus 6:2-11:10, principally serves to show the greatness of God the Father through Jesus as His messenger. This part is to show the magnificence of the stronger contractor of the covenant, His ability to act as a defender of the weaker partner. As in Ex 6:2-11:10 regarding Moses and Aaron, the Evangelist convinces the reader of this part of the Gospel about the credibility of Jesus as God’s representative and simultaneously the One who leads people to Him, to eternal life.

Just as Egyptians are shown in Ex 6:2-11:10 as the enemies of true God and Israelites, so analogically is with Jews of Jerusalem in this pericope. Namely, they are shown as opponents of Jesus. As a result of their hearts’ hardening, they do not see His messianic mission concerning them and therefore try to kill Him. One must notice that the word Ἰουδαῖος (Jew) is mainly in two pericopes, namely: 47 times in Jn 1:19-12:50, mostly to describe Jesus’ discussions/disputes with Jews, and 22 times in Jn 18:1-19:42: Jews cause the killing of Jesus; Jesus is sentenced as the king of Jews.

The analogy to Ex 6:2-11:10 is evident in the similarity of the role of the signs-plagues of God in Egypt (the noun τέρας: 4 times; σημεῖον: 7 times) and the signs-miracles of Jesus (the noun τέρας: 1 time; σημεῖον: 16 times), and in the hardness of the heart of Pharaoh and his servants, and the hardness of the Jews of Jerusalem. Moreover, there is a similarity in the summaries of both pericopes: despite showing so many signs, the opponents did not believe – Ex 11:10 and John 12:40 – because the Lord hardened (the verb σκληρύνω in Ex 11:10, πωρόω in John 12:40) their heart (καρδία):

| Ex 11:10: | Moses and Aaron had performed all these miraculous signs and wonders before Pharaoh. The Lord hardened Pharaoh’s heart, and he did not want to send forth the sons of Israel out of the land of Egypt. |

| Μωυσῆς δὲ καὶ Ααρων ἐποίησαν πάντα τὰ σημεῖα καὶ τὰ τέρατα ταῦτα ἐν γῇ Αἰγύπτῳ ἐναντίον Φαραω˙ ἐσκλήρυνεν δὲ κύριος τὴν καρδίαν Φαραω, καὶ οὐκ ἠθέλησεν ἐξαποστεῖλαι τοὺς υἱοὺς Ισραηλ ἐκ γῆς Αἰγύπτου. | |

Jn 12:37: | Although He had performed so many signs before them, they did not believe in Him. |

| Τοσαῦτα δὲ αὐτοῦ σημεῖα πεποιηκότος ἔμπροσθεν αὐτῶν οὐκ ἐπίστευον εἰς αὐτόν | |

Jn 12:40: | He has blinded their eyes and hardened their heart so that they might not see with their eyes and understand with their heart and be converted, and I would heal them. |

| τετύφλωκεν αὐτῶν τοὺς ὀφθαλμοὺς καὶ ἐπώρωσεν αὐτῶν τὴν καρδίαν, ἵνα μὴ ἴδωσιν τοῖς ὀφθαλμοῖς καὶ νοήσωσιν τῇ καρδίᾳ καὶ στραφῶσιν, καὶ ἰάσομαι αὐτούς. |

B. Jn 13:1-17:26. Jesus’ Passover Supper with the disciples. As in Ex 12:1-13:16, where the law of Passover/Covenant is shown, so here is the law of Eucharist/New Covenant, the law of service out of love to brothers, the law of closeness to Jesus, the law of opening to Father and the gift of the Holy Spirit. Moreover, as in the history of Exodus from Egypt, it was the Supper (eating a lamb with unleavened bread and bitter herbs) at night that directly preceded the long-awaited moment of departure (which is made present in the next, third part of the Passover liturgy), the same is true for Exodus of Jesus. Namely, the Passover Supper at night directly preceded the next stage of Jesus’ life, which was to set out on the way of passing through the Passion and Death. As already indicated above, it is evident that St. John intentionally extended – in opposition to the Synoptics – the description of Passover Supper. He did it to point out that Passover Supper’s description is one of the main four pericopes, the description of the second main stage of Jesus’ Exodus. It is because, in terms of the number of words (2822), the pericope of Passover Supper takes second place (the four successive middle pericopes have: 9790, 2822, 1609, 615 words). The Synoptics devoted incomparably less space to the description of the Passover Supper.

| The analogy between the pericope Jn 13:1-17:26 and Ex 12:1-13:16 is primarily evident in that they both represent the Passover supper before the departure. |

Besides, there are distinctive details that serve compositional purposes, but if the reader does not understand them, they make him concerned. Namely, in both pericopes, there is a short sentence about setting off from the place of the feasting, the sentence which does not being a report on the historical event (the setting off) but an element of the literary technique (literary inclusion), which closes part of the text and points it out as a logical whole. Namely:

(a) Ex 12:41-12:51 is the literary inclusion in which the inspired author says:

Ex 12:41 And it came to pass at the end of four hundred and thirty years, on that very day, all the hosts of the Lord went out from the land of Egypt.

וַיְהִי מִקֵּץ שְׁלֹשִׁים שָׁנָה וְאַרְבַּע מֵאוֹת שָׁנָה וַיְהִי בְּעֶצֶם הַיּוֹם הַזֶּה יָצְאוּ כָּל־צִבְאוֹת יְהוָה מֵאֶרֶץ מִצְרָיִם

καὶ ἐγένετο μετὰ τὰ τετρακόσια τριάκοντα ἔτη ἐξῆλθεν πᾶσα ἡ δύναμις κυρίου ἐκ γῆς Αἰγύπτου

Ex 12:51 And it came to pass in that very day that the Lord brought the sons of Israel out of the land of Egypt by their hosts.

וַיְהִי בְּעֶצֶם הַיּוֹם הַזֶּה הוֹצִיא יְהוָה אֶת־בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל מֵאֶרֶץ מִצְרַיִם עַל־צִבְאֹתָם

καὶ ἐγένετο ἐν τῇ ἡμέρᾳ ἐκείνῃ ἐξήγαγεν κύριος τοὺς υἱοὺς Ἰσραὴλ ἐκ γῆς Αἰγύπτου σὺν δυνάμει αὐτῶν

However, the departure in its historical aspect is described only in the next pericope, starting from Ex 13:17, while here, after Ex 12:51, is the second part of the pericope of law.

(b) Jn 14:30-31:

Jn 14:30-31 I will no longer speak much to you, for the ruler of this world is coming, but he has nothing of his own in me; but the world must know that I love Father and do as Father commanded. Arise (ἐγείρεσθε), let us go hence.

Here, too, Jesus and disciples do not leave the Upper Room; as in the Book of Exodus, their departure does not occur until the beginning of the next pericope. It is evident that this verse and 13:4 serve together as a literary inclusion for the first part of the pericope of the supper: both contain the word ἐγείρω – arise. Jn 13:4: He rose (ἐγείρεται) from supper and took off His outer garments.

We can even suppose that 13:1-4 with 14:28-31 constitute a literary inclusion for this first part of the pericope of supper because they deal with the same subject.

Jn 13:1-4 It was before Passover. Jesus, knowing it had come His hour of passing from this world to the Father, having loved His own who are in the world – He loved them to the end. During supper, when the devil had already put it into the heart (καρδία) of Judas Iscariot, son of Simon, to betray Him, knowing that the Father had given Him all things in His hands and that He came from God and goes to God, He rose (ἐγείρεται) from supper and took off His outer garments. Having taken a towel, He girded Himself.

We can see that the pericope of supper before the departure has two parts in both books, with the first part always ending with the second verse of such a literary inclusion that speaks about departure, although this departure will take place after the second part of this pericope, i.e., at the beginning of the next pericope.

C. Jn 18:1-19:42. Jesus’ passage through the Abyss of Passion and Death as the covenant-making in His blood. Ex 13:37-14:31 describes the act of definitive conclusion (in Hebrew: cutting) of the covenant through the passage of God, in the sign of fire/cloud, and Israel, the passage from the place of Passover supper to the sea and between its waters cut into halves. Analogically, John’s Gospel shows Jesus’ passage with His disciples from the Cenacle into the Garden of Olives, and from there through the Jewish and Roman judgments onto Golgotha, where He is dying in the presence of His Mother Mary, other women, and the Apostle John. From here, He descends into the Abyss to pass through it within three days until the Resurrection (which is the theme of the next main pericope). Although the Apostle does not speak here about the descent into the Abyss, it was apparent for the believing Jew because revealed in the Old Testament. It is visible in the apostolic teaching of St. Peter [41] (cf. Acts 2:27-31; 1Pet 3:18-4:6) or Paul (cf. Rom 10:6; Eph 4:9-10), and simultaneously confirmed, in a literary form more challenging to understand, by the Apocalypse of St. John (1:18; 6:8; 20:13-14).

D. Jn 20:1-20:31. The pericope of Jesus’ glory. Just as in Ex 15:1-21 Israel sings a hymn in honor of God as her King, mighty Protector, the One who overcame both power of Abyss and enemies of salvation, Egyptians, so the same is in this pericope of John’s Gospel which shows the power and glory of Jesus as the Son of the Father, the Risen One, who overcame Abyss-Death and the devil with his allies as enemies of salvation (cf. Rev 20:1-3). Just as in hymn, Israel is already in possession of Promised Land through the principle of anticipation, the same is with the glory of the eternal life of Risen Jesus in this John’s pericope. Jesus already gives His disciples the Holy Spirit [42], and hence eternal life – they participate in it now, through the principle of New Testament anticipation, even though they are still living in temporality.

One should note an analogy introduced by the Apostle John between the pericope of glory in the Book of Exodus and the pericope of glory in his Gospel. For in the pericope of glory in the Book of Exodus (Ex 15:1-21) is present Miriam (מִרְיָם – Μαριαμ) together with women not mentioned by name, preaching the glory of God immediately after the crossing the Sea Abyss. An analogical situation is in the pericope of glory in the Gospel of John: The Apostle writes here about Mary (Μαρία: Jn 20:1-2.11-19), to whom, as the first person, appeared Jesus, having just come out of the Abyss of Death; then, at Jesus’ command, Mary proclaims His glory to Apostles. The Evangelist intentionally does not name other women present near the empty grave; simultaneously, by using the plural in Mary’s statement – “They have taken the Lord from the tomb, and we do not know (οὐκ οἴδαμεν – Jn 20:2) where they put Him” – he points out that he knows about their presence, as the Synoptics say (cf. Mt 28:1-10; Mk 16:1-10; Lk 24:1-10.22-24). John somewhat says through this literary technique: “I know other women, but I do not name them so that my description would be similar to that in Ex 15:1-21”. In this way, he links two pericopes of glory – the one from the Gospel and the other from the Book of Exodus.

Thanks to Mary, the difference between the pericope of glory and the Epilogue is also visible. Namely, Mary is nowhere in the Epilogue, but only in the pericope of glory; the apostles are here and there.

Epilogue. All events in this pericope take place near the Sea of Tiberias, so where Jesus initially was calling His disciples. Unlike the previous pericope, which focuses on the extraordinary nature of Jesus’ Resurrection, the Epilogue shows Jesus caring about His disciples’ daily life: for food and establishment of pastoral authority in the community. At the beginning of the revelation and meeting with Apostles, Jesus turns to them through ‘children’ and asks them if they have something to eat. When it turns out that they have nothing (cf. Jn 21:2-3), He gives them an order; their obedient fulfillment of His will turns out to result in an abundance of catch. This situation is analogous to that described in Ex 15:22-17:7, being the first part of the last pericope of Ex 1-18. Namely, it describes Israel’s daily life after passing through the Abyss-sea and singing the glory to the Lord. When it turned out that Israelites have no water or food, God satisfied their needs through extraordinary interventions. God was in continuous dialog with Moses and with people through him so that they could present Him their scarcities. As the answer for their needs, He changed bitter water, not drinkable, into a sweet one, He started to bringing quails and manna, a gift from heaven, He also made the water gushed from the rock (see Ex 15:22: Israelites did not find water; 15:23: they found bitter water only; 16:3: their hunger; 17:3: they worry for food for children). Moses and people’s obedience to God, who gives them orders, is essential for satisfying their needs by Him.

The second part of the Epilogue shows Jesus’ dialogue with Peter, resulting in establishing the pastoral authority of the People of the New Covenant. The analogical situation happened in the penultimate part (cf. Ex 18:13-26) of the last pericope of Ex 1-18, where, on the advice of his father-in-law and apparently after receiving approval from God (cf. 18:23), Moses established a hierarchy of judges, with Moses as the main one, to settle matters between Israelites. This act is preceded by a meal in the presence of God (cf. 18:12). The same is true of the Gospel of John! – cf. Jn 21:15.

The third (i.e., last) part of the Epilogue is analogous to the last sentence of the last pericope of Ex 1-18. Just as Jethro departs from the assembled Israelites and returns to himself (Ex 18:27), an analogical situation now reveals (only now! – Jn 21:20). Namely, it turns out that Jesus, when he was speaking with Peter, was already departing from the Apostles, and John was witnessing this conversation because he was following them both. Now comes a passage mysterious – as the Evangelist himself points out – which is difficult to understand. Jesus’ statement about Evangelist, twice repeated here, “If I want him to remain until I come, what is that to you?” (Jn 21:22), is explained as not communicating that he will not die. So what does this sentence mean, so emphatically communicated by Jesus?

ἐὰν αὐτὸν θέλω μένειν ἕως ἔρχομαι, τί πρὸς σέ;

Looking at the whole of the Gospel, which this disciple wrote, one can suppose that this phrase refers to his remaining on prayer after the Eucharist. For the Gospel, with its essential part, made up of four pericopes, represents the four-element Eucharist, so the Prologue represents the time of preparation for its celebration, and the Epilogue represents the time of remaining with Jesus after its completion. The author of the Gospel discreetly, without imposing this practice to others, shows that the love of his heart for Jesus allows him to remain in prayer in waiting for His coming.

The first communities of disciples of Christ had the custom to continue the prayer after the Eucharist, as St. Paul (1Cor 11:26b) expressed in a sentence similar in grammatical construction [43] to the above:

τὸν θάνατον τοῦ κυρίου καταγγέλλετε ἄχρι οὗ ἔλθῃ.

One should notice that the Apostle wrote this sentence in the context of receiving Holy Communion during the Eucharist:

For as often as you eat this bread and drink the cup,

you proclaim the death of the Lord until he comes.

Further research should deepen the understanding of both the literary structure of St. John’s Gospel and its particular passages, including the latter. For exegesis should serve the faith of the Church community. The interpretation of Sacred Scripture, freed from the dominance of the historical-critical method in recent decades, notably its rationalism unable to understand the supernatural dimension of reality, should bear fruit in the spiritual life of the community of the Church [44]. Therefore, the biblical scholar should not only analyze the text but also propose a fuller reading to pastors so that it may be reflected in a renewal of the believers’ relationship with God.

Conclusion.

This article shows the purpose served by the absence of the words of consecration in The Last Supper Pericope (Jn 13-17), the words that are essential to make present the act of the New Covenant making. Finally, it is worth noting that St. John began this pericope with a description of Jesus washing the feet of His disciples and giving the commandment to love as He loved, and concluded with a prayer for the disciples to fulfill this commandment by His power, the One, who sacrifices Himself for them. This pericope, therefore, focuses on showing this commandment and the ability of the disciples to carry it out thanks to Jesus, with whom they are closely united in love, and who intercedes to the Father for them, so that the Holy Spirit will continuously accompany them in this task, making them one in love with God and with the brothers.

Of the Evangelists, only St. Luke passed on the words of Jesus about the New Covenant – Jesus gives disciples at the Last Supper the cup which is the New Covenant in His Blood being poured forth for them (cf. Lk 22:20: τοῦτο ὸ ποτήριον ἡ καινὴ διαθήκη).

In contrast, St. John wrote down the words of Jesus about the new commandment (Jn 13:34: Ἐντολὴν καινὴν δίδωμι ὑμῖν), which He gives to His disciples after washing their feet and at the same time immediately before the hour of pouring out His Blood. We must, therefore, understand the novelty of this commandment as an element of the New Covenant. At the heart of the New Covenant, it is such love for others, which one realizes according to an example of Jesus and by the power of union with Him, and which includes humble acts of everyday love (such as washing one’s feet), and a total gift of one’s own life for the salvation of others [45].

The article shows above all the typological relationship between the Gospel of St. John and the Book of Exodus 1-18.

Just as the Book of Exodus 1-18 is the covenant treaty which God made through Moses’ mediation with His people by means of the passage between the divided waters of the Abyss (Red Sea), so is with the whole Gospel of St. John. Namely, it is the treaty of the New Covenant, which God made through the mediation of His Only-begotten Son Jesus with His people by means of the passage between the divided darkness of another Abyss (Red Sea of Jesus’ blood), into which Jesus entered through Death on the cross.

Prologue is a historical introduction to the Lord Jesus’ activities, and in particular, to the four successive stages required by the ancient rite of the covenant.

- Just as God presented Himself in the Exodus of Israel through ten wonderful signs, so Jesus, through signs and miracles, reveals Himself and the Father who sent Him and in whose name He wants to make a New Covenant with humankind. In this stage, Jesus carries out the first stage of the covenant ceremony: the presentation of the covenant parties, and especially the stronger partner. The weaker contractor is also shown: in his physical and moral sufferings, in expectation of salvation from sin and death.

- Just as before leaving Egypt God through Moses gathered Israel together at the Passover supper of the Original Covenant, so Jesus before coming out of this World to eternity gathered the Apostles at the New Covenant supper, in which He revealed the law of the New Covenant: service, love for God and brothers, the law of giving life to save the brothers from eternal death. St. John does not inform explicitly by the words of the text that Jesus within the Last Supper makes the New Covenant in His Blood. One will be able to read this information no from verbal records but from analysis of the structure of the whole Gospel, including the significance of the third element of the Passover rite in light of the Book of Exodus 1-18.

- Jesus comes out of the Cenacle to pass through the next dramatic events to the Cross rammed in the rock of Hill of Golgotha outside the walls of Jerusalem, so that descend from it into the Abyss of Death.

- Jesus Resurrects, reveals Himself to selected witnesses, breathes the Holy Spirit on the Apostles gathered in the Cenacle.

Epilogue – through this easy to notice ‘clumsy’ (the end after the end) literary element, the hagiographer indicated that it is another basic part of his Gospel, the literary pericope. It has a role analogous to that of the sixth element of the literary structure of the Hittite covenant treaties, and also the sixth element of the literary structure of The Book of Exodus 1-18. It contains the most important laws for daily life, given by the Risen One as the stronger contractor of the covenant to the weaker contractor – to humanity, particularly to His disciples. Namely, Jesus calls them to believe that God feeds His children, expects their obedience to Peter as His appointed representative, wants the eucharistic community to remain on prayer after the liturgy until He comes to them as the Lord of Glory to give them the Holy Spirit.

One has proved in this article that St. John included in his Gospel the essential act of the Eucharist – the Transubstantiation – although he did so in a surprising way, different than the Synoptics. The words of consecration, present verbally in their Gospels, are present in St. John through pericope called The Book of Passion (Jn 18-19), describing the historical event of Jesus’ passing through the Abyss of Passion and Death as the act of the New Covenant making. The absence of the words of consecration in The Last Supper Pericope (Jn 13-17) serves to focus attention on the meaning of this part as a representation of the second part of Eucharist (i.e., the prayer of faithful). Consequently, it serves to understand each of the six pericopes and their role in the structure of the whole.